If it were only possible, the philosopher and thinker Dr. Micah Goodman, one of the most fascinating researchers of Jewish thought in our generation, would "fly-in" from the past the heroes of his first three books: the Rambam (Maimonides), Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, and Moses – so we could all listen to their wisdom on how the world and humanity are changing due to the coronavirus pandemic. Goodman (45) has dealt with these leaders a lot over the past decade, studied their work and legacy, and succeeded in his clear style to make them accessible to the Israeli public. But an imaginary meeting like that is, of course, only possible through their writings, and Goodman is an excellent mediator.

"Moses," Goodman believes, "would have demanded from us in the spirit of Jewish tradition to take something from these days for the future routine, the feeling of fragility and helplessness, which was a characteristic during his days of 'the enslaved nation'; to remember this time next year and not to forget how helpless, ignorant and limited we were with our knowledge and how we depended on each other."

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

Goodman thinks that recognizing and remembering all of this after coronavirus is behind us "is part of the medicine for this pandemic. The Rambam, who sanctified wisdom but also recognized its limits, prepared us in a way for the coronavirus era, since we will always live in a universe where we don't have a full and definite understanding of it. Science knows much, but it is not almighty – that is a complete 'Rambamist' conclusion. 'The Guide for the Perplexed' from the 12th century shows us how to live with perplexion – and in the corona era we are all perplexed, and so this great creation is relevant even more now. Rabbi Yehuda Halevy, who was rational, also recognized the limits of wisdom."

Goodman's wandering between Israel's sectors – religious and secular, left and right, and now human relations with technology (he is writing a new book about this) – is based not only on the present but on insights originating in the distant past. Together with the former head of Shin Bet Yoram Cohen, he is now drafting the "belief of the Israeli consensus" – according to him – on the issue of our relations with the Palestinians. His book, Catch 67, tried to remove Israelis from the "illusion of peace and the end of the conflict," but also from "the dreams of annexation". Goodman prefers a partial alternative, incomplete by definition, but many times more realistic in his opinion, which "the 'deal of the century,' with post–coronavirus adjustments, can work with." But now it's pandemic time, and in his home in Kfar Edumim, Goodman is focusing on "the great lesson" the virus has given humanity.

"Jewish tradition has always challenged its sons and daughters to experience reality in two different, parallel and at times contrary perspectives. The first – as humans, and the second – as Jews," he says. "As humans – the seminal narrative through which we experience the world is as God's creations, and part of the family of man created in its image. As Jews – the seminal narrative is the exodus from Egypt and national redemption. We are national patriots who see ourselves as committed to every Jews at the family, community and national levels.

"The Jewish challenge," he believes, "demands from us to live in two dimensions: to be universal and humanist people and also particular, nationalist and patriotic Jews. It's not necessarily contrary, but it doesn't always work out together. Some of my best friends, who define themselves as cosmopolitan and citizens of the world who feel empathy for all humans, tend to be embarrassed of their national affiliation and dilute their feelings of patriotism. On the other hand, the more you are a patriot and connected to your national roots – your universal feelings are diluted. This is where the Jewish tradition comes in and demands you to overcome this catch: Sabbath appears twice in the Torah; once in 'the memory of creation' and once in 'the memory of leaving Egypt'. Our Sages of Blessed Memory teach us: 'Zachor and Shamor were both originally said by Hashem simultaneously' and try to combine the two narratives. This is one of the greatest Jewish challenges that we consistently fail at – the combining of universality and nationality."

'Get closer through biology'

During the coronavirus era, Goodman says, something marvelous has happened, where we succeeded in creating something we thought impossible in the past: "My fears are the same fears of people in London and Brazil and Ramallah and Jericho. People from all over the world are feeling the same emotions, fearing the same fears. During a crisis we are used to fear other nations; the coronavirus is a revolution where we fear together with other nations. It's not 'us against the world' – which is our classic emergency feeling. During corona, it's 'we are one with the world.' This is a time of emergency that puts us together will all humanity and trains us to widen our empathy for all people. Ideologies may separate us, but biology binds us. We are part of the family of nations."

Q: And patriotism gets hurt?

"Not at all. The opposite. More than before, people have a feeling of high national solidarity. The corona broke the zero sum feeling between universality and nationalism. It lets us experience both sides of our identity – Israelis and humans at the same time – Zachor and Shamor simultaneously."

Q: The sociologist and philosopher Prof. Shmuel Trigano, in an interview given to this newspaper a month ago, talked of "the end of globalization," and that "the coronavirus is forcing all countries to return to the nation-state, orders, closure, strengthening of the collective identity of each nation."

"In certain ways, yes, but I'm speaking of feelings that generate identity, and on that level, we are experiencing the same feelings together with other nations. On the level of feelings, this is super–globalization. The historian Prof. Benzion Netanyahu, the prime minister's father, saw the connection of nationalism and solidarity between nations as the seminal idea of Herzl and Jabotinsky; organizing all the Jews in the framework of a nation-state, without seceding from humanity, but with blending into the family of nations, and that is what is happening now: we are patriotic Israelis who feel emergency together with humanity and not against it, as we've gotten used to. It's a rare and unique lesson. For a moment we have been freed of the binary."

Q: What has the coronavirus done to us in terms of time and space?

"Part of human nature is to deny human nature. People tend to deny their own limits. Modern western civilization worked to cancel the limits of space. Once the saying 'Man is nothing but the shape of his native landscape' was the answer to the question 'who are you' and not 'where are you?' Globalization separated between place and identity. It pretended to determine that man belongs everywhere. The coronavirus turned the wheel back. Man is again the shape of his native landscape. It reminded us that we are local. Personally, four of my lectures abroad were canceled one after the other, and then two lectures in Israel, and in the end, like all of us, I socially distanced myself at home. I returned to being 'local'."

Many, he notes, felt that "western civilization is a culture that denies death and finality, not as a theological claim but as a life experience: we do not feel comfortable with death. The elderly are put far from sight. Large billboards are with pictures of young people. We are a society that admires and glorifies youth. The inflation in technological simulations, which are a trait of our generation, is part of the forgetting of our finality. It is a consistent distraction from the human existential state."

Q: And then the pandemic comes.

"And suddenly we stand in front of death, and fear that people we love will die. Companies\Societies start to collapse and we are exposed once again to the reality of finality. The coronavirus cracks our death denial mechanisms. It places before our eyes once again the temporariness of our existence here, and reminds us that we are locals and that there is an expiration date on our existence. It puts humanity in front of its own humanity. I believe this is yet another great lesson, because the moment we stand in front of our humanity; the moment we rediscover that we are locked in time and space and cannot deny our humanity – that is the moment we understand that our time here is limited; that time and place have much more significance than what we gave it before. That understanding is a possible means for regrowth of spirituality and morality."

'Old age is not rock bottom'

Goodman speaks of a third important lesson, connected to the orthodox society. "The fact that a minority in the orthodox society reacted slowly to the virus caused – at least during the first stage – a high rate of infected and ventilated amongst the ill," says Goodman, "this reality as we know caused anger and awakened all the anti orthodox demons that exist in certain parts of Israeli society, but alongside what critics of the orthodox society call weakness I choose to learn about their strength.

"I recently read two books on the orthodox society, by Benny Brown and Haim Zicherman, and I learned from them about three important traits of this society – obedience to the Giants of the Generation, extreme conservatism and objection to innovation and changes, and also a great effort to steer away from modern Israel."

Therefore, Goodman explains, when asking why the orthodox reacted so late to the virus – the answer is first of all obedience. "Rabbi Kanievsky said something, and many obeyed the Giant of the Generation. The fact they responded slowly should not surprise anyone. It is a society whose ideology is to change slowly, 'new is forbidden by the Torah'. Their intuition is not like modern people. Orthodox sanctify lack of dynamism. The old is holy. Finally, there is seclusion from Israeliness. When the rules for behaving differently, emergency rules, come from the same society that all these years orthodox are secluding from, it's much more difficult to follow those rules. The orthodox society became, in this case, a victim of the three elements it has followed for many years."

But now Goodman wants "to add another level to looking at orthodox society. The question is not only how to critique the orthodox community, but the question is also, what can we learn from the orthodox society," and claims there is a fascinating double paradox concerning this community. "The first paradox: the society that sanctifies the old and ancient is the youngest society in Israel; and the second paradox: the nonorthodox society, the aging one, sanctifies and glorifies youth. Once, when youngsters wanted to improve their status, they dressed older. Today western society behaves the opposite, older people try to dress and speak like youngsters to improve their status. On the other hand, the orthodox society behaves differently. Despite being young it actually admires older people and the elderly. Orthodox culture doesn't see the age of 20 as the peak of life like western society does. The opposite: it sees 80 as the peak of life."

Goodman claims that a society that admires and sanctifies youth pays a psychological price, since it creates an emotional and depressing experience of time. "After 20, with every day that passes – you get further from the peak. But in orthodox society, with every day that passes you get closer to the peak, not further. Historically – against the background of the orthodox belief of the 'lessening of the generations,' which sees the current generation as lower than the generation of 'the greats' of the past – the orthodox society is experiencing a process of degeneration, since it is getting further from the sanctified past, but biographically – its life is one of evolvement and growth, since old age is seen as the peak and not the bottom."

All these insights, Goodman admits, make him feel "jealous of the orthodox society. The fact that this society admires and respects old age – it's a huge advantage in my eyes. I want to use this virus not only to critique the orthodox, but also to learn from them. Each tribe has something to teach, and the virus has challenged the western society on one of its weak points and made us sacrifice for the older population at risk. It's an important reminder."

'Part of human nature is to deny human nature'

Q: The pandemic perpetuated the state in our lives. Suddenly when a person got sick, it wasn't their own private issue.

"I am concerned with the possibility that when we look back and ask ourselves what we learned from this time, we'll find out that the more the state was more authoritative, the better it dealt with the disease, and the more society was freer, it failed in dealing with the disease."

However, he estimates that "the technological developments and medicines and vaccines for the pandemic will come from the open and free societies. It's more probable that authoritative societies will succeed in preventing more harm and that open societies will be the ones who find the solutions. This is the tradeoff between freedom and security. Living in a democracy is daring to live with a lot less certainty in order to enjoy freedom. Therefore, when people are afraid, they're willing to give freedoms to the regime in order to get more security. In that way, the history of Israel is a miracle. Despite the state of emergency it is in, since its founding, it still safeguards the rights of its citizens to a considerable extent. In regards to the coronavirus, I admit I don't like the possibilities of digital surveillance. The health dividend of this surveillance does not justify the danger it poses to freedom."

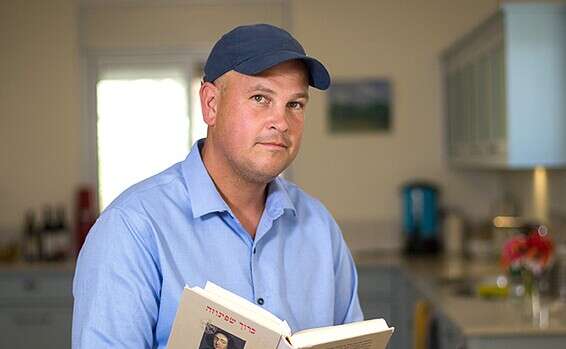

Goodman, is a research fellow at the Hartman Institute and lecturer at the Elul Program in "Beit Prat – Israeli Midrasha" (whose management he handed over three years ago to Anat Silverstone), and was born to American parents, Gary Goodman and Maggie Love. His mother was Catholic with native American roots, in the Chickasaw tribe. She converted and made aliyah to Israel with his father after the 1967 Six-Day War. He grew up in Jerusalem and in the last decade published his five books (Maimonides and the Book That Changed Judaism: Secrets of 'The Guide for the Perplexed'; Kuzari Dream; Moses's Final Speech; Catch 67; and The Wondering Jew: Israel and the Search for Jewish Identity) which made many waves.

In June 2014 Goodman was awarded (together with musician Ehud Banai) the Liebhaber Prize for the promotion of religious pluralism and tolerance in Israel given by Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies. He has dialogue and keeps in touch with the Catholic branch of his mother's family. Once he clarified, in an answer to a question, that when he looks at his wider family, anyone who tells him that just because they aren't Jewish they are lesser than Jews sounds ridiculous to him: "They are good, sensitive, gentle, holy, God-fearing people."

He also says that "religion in extreme doses brings out the worst in people. And complete disbelief does not bring out the worst, but does not allow for the pushing of the good buttons that religion pushes. So I believe in small doses of religion. In the possibility not to bring out the monster in people and at the same time to polish and refine it, to bring out the best of it."

These days he's also dealing with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, as a continuation to Catch 67. "One of the characteristics of our thinking about the virus," Goodman connects between the conflict and the pandemic, "is that we don't try to make it disappear. Experts from around the world are trying to find a formula that will balance between safeguarding the health system without ruining the economy, and between saving the economy without ruining the health system. There are differences, but the argument is not absolute. Nobody is saying that the aim is to prevent death. There will be dead. Nobody is pretending to prevent unemployment. There will be unemployed. The leadership is not trying to make these problems disappear but to avoid two tragedies."

Goodman is trying to implement this vision for the conflict. "We've gotten used to thinking about it in a utopian manner, looking for a solution that will bring an end to violence. One side in the internal argument over the territories tries to prevent the demographic danger of a binational state, and the other side tries to prevent the security danger in withdrawing to the Green Line."

Goodman wants us to "think corona," and asks each side in the argument to treat not only "the threat they think is more severe," but also "the threat the other side thinks is more severe. Maybe the coronavirus can cure our thinking and teach us not to ask how the problem will disappear, but ask – how to avoid a disaster. Ask what the right move is. Instead of considering only one disaster, seriously consider both disasters simultaneously."

"The right move," he believes, "can be found in Trump's plan. You only have to take out of it the utopian clauses of the left – signing a peace agreement and the finality of the conflict, and give up on the utopian dream of the right – annexation. Without those, the plan will become an effective mechanism that will prevent deterioration into one state and loss of a Jewish majority, without the danger of losing security as a result of a dangerous withdrawal."

In his opinion, "the Deal of the Century in a post–corona version will create optimization of both Israeli wishes, which are allegedly opposed: it will considerably minimize the size of Israeli rule over Palestinians, without minimizing security for Israelis. It will give the Palestinians a 'minus state' and the Israelis true security, since the freedom of movement and action of the IDF will be kept in the Palestinian territory and around it. Instead of talking about the size of land that will be given, let's talk about the size of sovereignty. Instead of talking about the amount of land we'll annex, let's talk about the amount of security we'll create. The coronavirus is telling us: there are two possible disasters. Let's minimize both of them. We can use that language in the conflict, as well.