New cartoons from the Arab media – that's how Noam Bannett starts his day. Not that this habit is at all soothing – the cartoons in the Middle East are not known for their good taste or subtlety. But that is precisely why they're important. Their perspective is like a finger on a pulse, and the pulse of the Arab world and the world of Islam is far from tranquil.

Bannett is a researcher and lecturer on the Arab world and Islam and is an expert on cartoons from the Middle East. He ended up focusing on the edgy illustrations by chance. "During my first years in teaching I tried to stimulate the students' interest in the Middle East and would send them a cartoon every once in a while and ask them to analyze it. I slowly created a growing stockpile of cartoons from the Arab world, and I realized that they can show the crux of events occurring in the region and the world.

At first, they were like a spice, but in time, became a meal in itself, since the cartoon has the power that opinion pieces or essays don't. Thanks to social media, with the right tagging, I discover through them what is going on in the Muslim world - it's as simple as that."

Follow Israel Hayom on Facebook and Twitter

The art of cartoons has been a barometer of modern society long before the appearance of social media, and the price of its influence has always been high. In the late 1980s cartoonist Naji al-Ali, known for his Arab nationalist views who just three years earlier was described by the Guardian as "the nearest thing there is to an Arab public opinion", was murdered in London.

Bannett says, "He created the cartoon character of the Palestinian refugee. In a way, he was the 'Srulik' of Arabs in Israel. Like his character, Naj al-Ali became a symbol of the Palestinian struggle against Israel in the Arab world, however, he never hesitated to critique [then-PLO Chairman] Yasser Arafat and other internal figures of power, portraying them as hedonists and corrupt. In fact, some believe that Arafat was the one behind his killing. Many Arab cartoonists, certainly among the Palestinians, see themselves as his successors."

The venom and enmity dripping from his cartoons continued to be expressed after his death. For example, al-Ali used to use motifs of crucifixion to drive hostility towards Israel and sympathy for those fighting it. Since then, that motif, based on the ancient anti-Semitic trope, is deeply seeded in anti-Israeli propaganda.

Q: Who are the most influential cartoonists in the Arab world today?

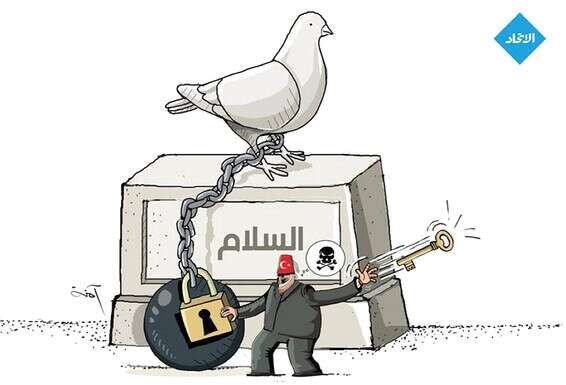

"Al-Ali's line is being continued by two Gazan cartoonists – Omaya Joha [real name Omaya Abu Hamada], a Hamas supporter, and Alaa Al-Lakta, and also by a Jordanian cartoonist born in Ramallah, Emad Hajjaj. An interesting anecdote is that two months ago, Hajjaj was arrested by Jordanian authorities, after posting on his Facebook page a cartoon against the peace agreements between Israel and the UAE. This cartoon insulted Mohammed Bin Zayid, the Emirate Crown Prince and the strongman of the country; in it, he's depicted holding a peace dove with an Israeli flag, but the dove is spitting on him with the saliva shaped as a plane, on which it says in Arabic 'Spit-35'. One can only assume the patrons in the UAE hinted to the Jordanian king that this type of insulting cartoon is not acceptable.

"The arrest created a wave of cartoons demanding the release of Hajjaj and dealt with freedom of expression, or the lack of it, in the Arab world. The peace agreements created a wave of Palestinian cartoons against the Emirates (one of them even depicted the crown prince as toilet paper), but if anyone thinks that Hajjaj's cartoon was moderate in western terms, they should remember that the spitting motif is not something minor, when the target is a powerful regional Arab leader like Mohammad Bin Zayid."

Q: We've become accustomed to the cartoons against Israel, as offensive and false as they may be. But it's odd to find these harsh critiques in cartoons that display the internal Arab debates.

"The great cartoon festival is taking place now over struggles in the Arab world, just like the struggle now between the UAE and Qatar, or the wider battle between the axis that includes Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain and the UAE with the axis of the Muslim Brotherhood, Turkey and Qatar. Both sides are not reining in their tone.

"On the one hand, Saudi cartoons dwarf Turkish President [Recep Tayyip] Erdogan and portray him in miniature (even though he's one of the taller leaders in the Mideast), they mock the economic situation in his country or portray him and Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, the leader of Qatar, dancing together in Israeli clothes. On the other hand, there are cartoons that attack the Saudi crown prince Mohammad Bin Salman over the murder of journalist and member of the Muslim Brotherhood Jamal Khashoggi and often use motifs of a saw and sawing of bodies."

Q: In the latest cartoon scandal concerning the prophet Mohammad, which culminated in the beheading of a teacher who showed it to his students in France, the Muslim world was united.

"True, on this issue, there is a united front. It may sound simplistic, but to them insulting the prophet is like insulting a mother, it's unacceptable and makes the Muslim world stand on its hind legs with a message of 'a line has been crossed.' The determination of French President Macron to insist on freedom of expression in his country, even at the cost of insulting Muslims, has created a wave of cartoons against him in the Muslim world.

"In one of the more disgusting ones, from Yemen, Macron is portrayed as feces. And despite all these emotions, it doesn't hide the internal struggles in the Muslim world. After Erdogan spoke of Macron as someone who needs a mental test, the cartoonists from hostile countries to Turkey mocked Erdogan, not Macron. Someone from Lebanon reacted with a picture of the Turkish president in a room full of his portraits, hinting at his megalomaniac tendencies."

Q: What are the red lines in Arab cartoons?

"They won't draw the prophet, of course, not even in a positive context, since Islam forbids illustrating him. There are, for example, drawings hundreds of years old depicting the beginnings of Islam where the prophet is portrayed as a flame. But as a human with a face - no, and this is opposed to other figures, such as Ali in the Shia Islam, the prophet's cousin, who is illustrated. Beyond that, the cartoon allows creators to go wild. The other red lines have to do with the publication location. A cartoonist in Syria under Assad will not dare draw a cartoon against him or his allies. But if it's somewhere safer, like the UAE, you'll see a cartoon portraying Syria as a piece of meat in a butcher shop, and three butchers slicing it up, one with a turban, one dressed as a Shia religious leader, and the other in a Russian military uniform."

Mocking every US president

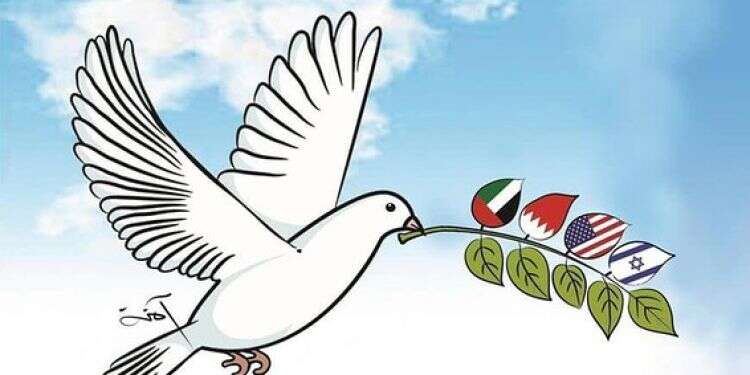

As could be expected, the world of Arab cartoons did not stay silent over the recent normalization agreements in the region. Unsurprisingly, the tone of cartoons was directly connected to the country they were published in and the identity of the cartoonist. The Palestinian cartoonists expressed the feeling that their brothers betrayed them and drew the peace dove as a trojan horse. On the other hand, the countries normalizing ties with Israel had their views, too.

"They dealt less with portraying the peace in a positive light, and preferred to attack the attackers," says Bannett, who writes a popular blog called "Window to the New Middle East" where you can see cartoons on various issues, even those not connected to politics. He is in contact with a few Arab cartoonists but refuses to go into detail, so as not to endanger these links.

"And despite this," he adds, "there are cartoonists who switched sides, did a sort of rerouting to a more Israel friendly direction. I believe the move was an instruction from above. Sometimes it's the exact same cartoonists who just months ago compared Israel to Iran, their greatest enemy. Now they're expressing a more positive attitude towards us, especially in the UAE. The change is combined with the more general trend in the UAE to create an image of tolerance."

Geopolitics played a role also when the world learned Donald Trump contracted the coronavirus. Most of the Arab cartoons mocked Trump, and some distorted the face of the American president to make it look like the virus. On the other hand, a cartoon from the UAE praised his quick victory over the disease.

As long as the cartoon is seen as an effective weapon in the propaganda arsenal, the leaders will decide the target. Only the topic will change, as long as the daily stories will provide the typical Arab cartoonist some sort of newsworthy interest. In this context, quantitative analysis of cartoons can show the intentions of the regimes. "I noticed a rise in the number of cartoons in the UAE mocking Erdogan even before the worsening in relations between these countries due to the peace agreements with Israel," explains Bannett, "but if we focus on the pro-Palestinian camp, then any US president is target for mockery of a cartoonist."

A troubadour with a paintbrush

The lecturer on Oriental studies, Idit Bar, who writes the blog "Idit's weekly cartoon" explains that most of the cartoonists in the Arab world on politics are men: "There are female cartoonists in Arab states, but most of them deal with social and cultural issues and less with politics. The cartoon in the Arab world has a lot of power. It's powerful and shapes opinions, and even calls to action. I wouldn't be exaggerating by saying that it has magical influence. The cartoon, with its visualization and critique manages to touch the soul of the Arab and shake and shock him at times. There's a reason I begin my lectures with the expression a picture is worth a thousand words, but a cartoon is worth a thousand pictures."

Q: What is so unique about the cartoon in the Arab world?

"It's unique in two aspects: the huge stage it is given and the power of its messages. The Arab newspapers give cartoons a special place. There are newspapers that employ top-notch cartoonists, the most skillful there are. The brush that Arab cartoonists hold is a sort of weapon.

"The cartoonist sometimes critiques internally, he sees himself as an emissary of the oppressed public, and laments the social and economic situation, and at times the critique is towards hated rivals outside. It was President Truman who once asked what he was afraid of. 'I'm afraid of two things – death and cartoonists,' was his answer."

Bar describes how the president of Syria, Bashar Assad, took care of two Syrian cartoonists during the first days of the Arab Spring and the uprising against him. The cartoonist Ali Farzat dared to critique the murderous Syrian regime towards its own people, and in August 2011 paid the price. Masked men attacked him on his way home from the newspaper at night, beat him up and broke his fingers so he wouldn't be able to draw again.

A very strong cartoon showed his broken and bandaged fingers where the bandages fall from his hand and each finger holds a brush in a show of determination to continue and draw cartoons bravely. The fate of another Syrian cartoonist, Akram Raslan, was worse. In 2012 he was arrested by Syrian security forces for cartoons attacking Bashar Assad. In his case, the torturers did not suffice with breaking his fingers, they tortured him for a whole year until he died.

Bar has an interesting explanation for the source of power of cartoons: "In pre-Islamic Arab history there was a phenomenon of 'poet battles'. The troubadour of each tribe composed mocking poems for the rival tribe, and that's how they fought each other with words as an appetizer before fighting with weapons. The poet who composed the most mocking poems and succeeded to beat his rival raised the morale of his tribe and they usually also won the battle.

Subscribe to Israel Hayom's daily newsletter and never miss our top stories

"These days, the power has moved to visual images, to cartoons. With cartoons one can insult the rival and portray him as defeated. The cartoons can portray a military defeat as a victory, just as Arab cartoonists do after operations against Hamas, and as Egyptian cartoonists did after the Yom Kippur war."

However, cartoons also have much influence on social and gender issues – they can lead to social change. Cartoons had a large part in ridiculing the ban of women from driving cars in Saudi Arabia. Many cartoons were published mocking the law prohibiting women from driving, until Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz was forced to cancel the unique ban.