"God gave me this role at this moment," President Isaac Herzog told Politico this week. But his dilemma regarding a pardon for Netanyahu is one even the devil himself couldn't have devised. One camp believes the president's historic role is to rescue Israel from a trial that should never have happened and that has turned our politics into a religious war. The other camp believes Herzog's duty to future generations is to uphold the principle that "everyone is equal before the law."

In short, an out-of-the-box framework is needed. Over the past week, the President's Residence has turned into a laboratory of ideas — what the high-tech world calls a "hackathon": everyone arrives with their own clever patent.

If I may also propose one, voluntarily: to craft a solution, one must first understand the problem.

In his pardon request, Netanyahu speaks of two key issues: the first is the rift in Israeli society, which the trial has deepened. The second is the diversion of the Israeli prime minister's precious time in the middle of a period of unprecedented security and diplomatic risks and opportunities.

One of his well-known opponents told me this week that the rift will not heal if Netanyahu receives a pardon. Rather, in the eyes of the opposition it would deepen, as it will forever seem that he received an unfair advantage from the President's Residence.

So, here is the proposal for how to have the cake and eat it too, more or less: Netanyahu was indicted in three cases. The gifts case — Case 1000 — considered by the prosecution to be the strongest and most muscular of them all. The conversations with Arnon Mozes — Case 2000 — for which the prosecution agreed to completely drop the charges as part of a plea deal. And the Bezeq-Walla affair — Case 4000. The court made its view clear when it recommended that the prosecution withdraw the bribery charge, but one of Herzog's great frustrations, which led him to consider a pardon, is the prosecution's proud refusal to even consider the recommendation, thereby prolonging the trial endlessly — and for no purpose.

The right step for the president to take is to pardon Netanyahu on the bribery charge in Case 4000 and the fraud and breach-of-trust charge in Case 2000. In doing so, he acts both beyond the strict letter of the law and within it. Herzog would essentially be giving presidential approval to what is nearly a legally established fact.

How does this serve the interests mentioned in Netanyahu's request? It's simple. Netanyahu has already finished testifying in Case 1000, and once he receives a pardon for the other two charges, his testimony would no longer be required, and he could devote himself fully to national duties. Even if a breach-of-trust charge remains in the Bezeq-Walla affair, his testimony could be spaced to once a week, avoiding the madness in which the IDF chief of staff meets with the prime minister until one in the morning on Sunday, because the next morning he starts three consecutive days of testimony.

This would not widen the national rift, because this is not a celebrity freebie. It would shorten the trial by more than a year, dramatically cut the time needed for closing arguments and the writing of the verdict, and lead to a faster judgment. Paradoxically, the pressure to reach a plea deal would only increase, because the moment of truth — with all the heavy risks it poses to both sides — would draw near. If the president cannot end this nightmarish film, he can at least press the fast-forward button.

"It's no longer yours"

Rain dripped through the burnt roof beams of Amit Soussana's house in Kibbutz Kfar Aza. Already in November 2023, a month after the massacre and Amit's kidnapping, it was clear that not much would survive in the ruined homes without a comprehensive preservation plan.

More than two years have passed, and almost nothing has been done on the ground. Because even before the question of how to preserve, the question of whether to preserve arose. The residents of the three kibbutzim most devastated in the massacre — Be'eri, Kfar Aza, and Nirim — approached negotiations with the government with suspicion and mistrust. This is, after all, the government under whose watch they were slaughtered and kidnapped, and many in the kibbutzim did not want it or its representatives to determine how the massacre would be remembered.

This week, Kibbutz Be'eri voted on what and how to preserve. 102 members of the kibbutz were murdered by Hamas — a horrific number that put every option on the table, from preserving nothing to turning the entire kibbutz into a memorial site. By a vote of 196 to 146, they decided to preserve one house and demolish the rest. Another option discussed was moving the burned houses to the Nova festival site in Re'im with the same technique used to relocate the historic Sarona homes in Tel Aviv. Remembering and forgetting.

It is hard to characterize the identities of the "for" and "against" camps in a kibbutz where there is hardly a home without death. But residents noted that the main opposition to preserving more houses came from the Zeitim neighborhood, where many second-generation families with young children live. Their parents, who lived in the HaKerem neighborhood near the fence, were murdered in large numbers. The thought was that the grandchildren would not be able to run on the lawns with the smoking remains of their grandparents' homes behind them. Others voiced a similar sentiment: "We don't want to live in Yad Vashem."

How can one argue with someone whose experience is so horrific? Among government critics and members of the kibbutz, some nonetheless believe differently. A well-known left-wing public figure visited Be'eri recently. "It's no longer yours," he gently told them. "It belongs to the people of Israel." His words echoed what the American Secretary of War said at Abraham Lincoln's deathbed: "Now he belongs to the ages."

Is it possible to do both? One option proposed by the Heritage Ministry was called "the exception": only the houses near the fence would be preserved, creating a buffer from the rest of Be'eri; perhaps even the kibbutz fence would be moved. This way, visitors could come to the preserved homes in their original location without walking through the kibbutz itself.

Even after the vote, nothing is final. It turns out that under Israeli law, the final decision does not necessarily belong to the kibbutz residents. The Antiquities Law states that an "antiquity is a human-made asset from 1700 CE and earlier, of historical value, which the minister has declared an antiquity." The minister, the law says, may expropriate an antiquity site if expropriation is required for preservation or research. It is hard to think of late-20th-century kibbutz homes as "antiquities," but on the other hand, there is no doubt that even hundreds of years from now the events of that Simchat Torah morning will be remembered.

It is a tragic circle: Antiquities Authority staff worked in the homes, using archaeological methods to locate the remains of victims whose traces were almost gone. Now they may return as visitors to a historic site.

Heritage Minister Amichai Eliyahu holds this authority. He faces several obstacles. The first: this clause has never been used. The second: Eliyahu is a rabbi from the Otzma Yehudit party, and such an action could be perceived as a forceful act of annexation and expropriation by a religious nationalist minister against secular kibbutzniks.

So Eliyahu is weighing the move. Perhaps others — those without a political stake or bias — should speak as well. For example, the President of Israel. This dilemma is not only that of Be'eri's residents or the minister; it is all of ours.

Beyond bad taste

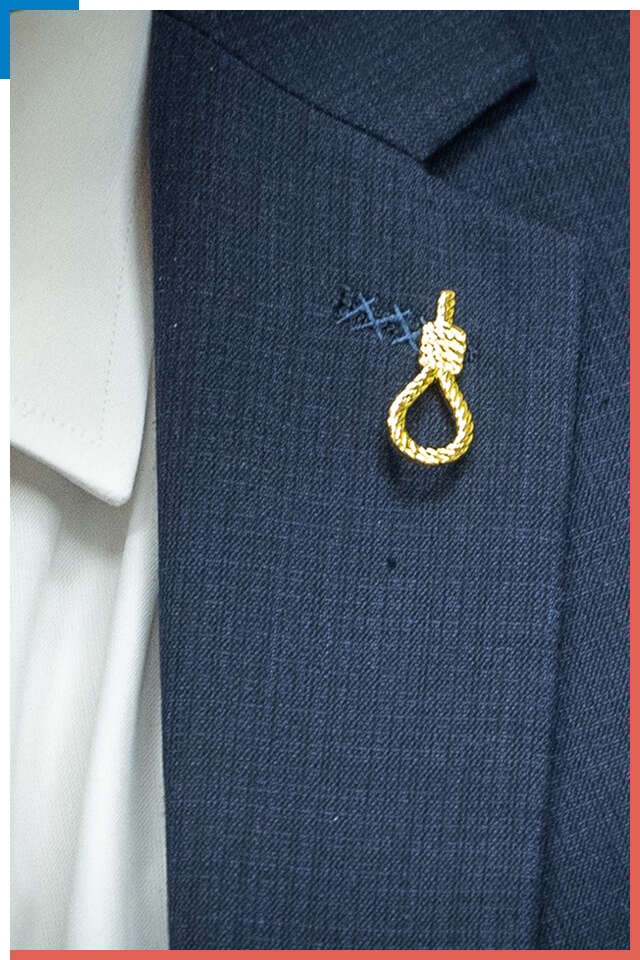

I tried for two days not to comment on National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir and his Otzma Yehudit party's golden noose pin. I've finally cracked.

Everyone knows why a bride walks under her wedding canopy, and yet no one says so out loud. Everyone knows that to carry out an execution you need gallows, and yet a reasonable person would not wear a hangman's noose on his lapel. This is why the Israel Defense Forces—unlike certain German armies of years gone by—does not put skull emblems on its uniforms, even though the IDF is responsible for quite a few Hamas corpses.

The Minister of Environmental Protection wouldn't wear a golden toilet bowl even if she was responsible for public restrooms, just as the emergency response organization ZAKA's emblem is not body bags.

When Nazi Adolf Eichmann was executed in 1962, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion wanted the death penalty imposed—and yet, old-fashioned as he was, he didn't walk around with Ben Gvir's pin. A weak leftist, clearly.

Beyond the bad taste, beyond the enormous harm to Israel's image when a member of the coalition wears such an emblem, it reflects a misunderstanding. Someone here has gravely confused the means with the end. The death penalty is a means; protecting Jewish lives is the end. Or maybe, actually, for Ben Gvir, the end is increasing his Facebook likes?

A good faith deposit

One of Benjamin Netanyahu's skills is conveying something without ever saying it publicly, on camera, or on the record. For example, he never publicly spoke about a partnership with Ra'am, even though he courted Mansour Abbas and met him at his Balfour residence more than once. This allowed him to attack Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid for bringing Ra'am into their coalition.

And so, when he stood this week at the Knesset podium to defend the Haredi conscription law, it was a pivotal moment. For the ultra-Orthodox parties, the prime minister's statement was the closest thing yet to a public commitment to pass the law. Until now they suspected — after all, they know their client — that the goal was merely to buy time. Now they know he is with them.

In conversations in his office, Netanyahu is already asking what the political cost of the law might be at the ballot box. This week, for example, he wondered whether, if the legislation passes in a month and a half and elections are held six months later, that is enough time to move on to other topics. So yes, he wants a draft law, yes, he wants a budget, and yes — he prefers elections in September 2026.

Only one small question remains: how to get the law past the Supreme Court. After all, it became clear this week that Boaz Bismuth's bill will not be greenlit by the Knesset's legal adviser. In such a case, an interim order will likely strike down the law immediately after it is passed — so what's all the effort for?

Unless — contrary to all the angry denials — the Haredim have more wiggle room in negotiations than they admit, and there is a whole herd of goats hidden in it. In other words: what has been submitted is not even close to the limits of Shas and United Torah Judaism's concessions. After all, this week their demand to recognize civilian national service as part of the quota was taken away, and they still continued negotiating. The committee's legal adviser speaks about raising the quotas, and they are not flipping tables.

Even MK Meir Porush, who declared that this law "must be torn up," is not viewed within the coalition as someone who will vote against it. And anything torn, as we know, can be glued back together.

And even if it is struck down, Shas and UTJ have a paramount interest in passing a law so they can return to government ahead of an election cycle that could lead to another one, and another. Their need to pass a budget has also become sharper in light of the High Court's rulings. There are a thousand paths for money, and MK Moshe Gafni walks them with the skill of a Bedouin tracker. So they grit their teeth and keep going.