Just hours after Delta Force commandos burst out of the night into Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro's bedroom and seized him and his wife, US President Donald Trump stood in the corridor of Air Force One alongside Senator Lindsey Graham and began ticking off new targets. "Colombia? Sounds good to me." "Cuba is ready to fall." "Something has to be done about Mexico." "We need Greenland." All in rapid succession.

The White House soon issued a statement saying Trump was interested in purchasing Greenland before the end of his current term, describing the move as "a national security matter." It added that "the use of the US military is always an option."

Senator Lindsey Graham speaking while standing next to Trump onboard AF1:

"You just wait for Cuba. Cuba is a communist dictatorship that has killed priests and nuns. They've preyed on their own people. Their days are numbered"

🇺🇸🇨🇺 pic.twitter.com/NWcN3iZX1D

— Visegrád 24 (@visegrad24) January 6, 2026

Each of these countries comes with its own specific reasoning for American interest. Cuba has been a communist thorn in Washington's side since the Cold War. Mexico is home to the world's most powerful drug cartels. Colombia is responsible for producing most of the world's cocaine. And Greenland, the world's largest island, boasts strategic geography and rare earth minerals beneath its soil.

But the thread linking them all is the objective placed at the top of the White House's National Security Strategy: control of the Western Hemisphere, which the US has long viewed as its "backyard," ever since its regional policy was shaped under what became known as the Monroe Doctrine, established in 1823.

Trump's National Security Strategy outlines what it calls "the Trump addition to the Monroe Doctrine." After years of neglect, the document states, the US will reclaim primacy in the Western Hemisphere and prevent competitors from outside the hemisphere from deploying threatening forces or capabilities, or from controlling vital strategic assets. The obvious implication is pushing Russia and China out of the region. But the current list of targets appears to go further and could lead to a fateful confrontation within NATO itself.

Alongside efforts to anchor the administration's approach in ideology or strategy, Trump's domestic political situation also looms large. The Epstein affair continues to dog him and has triggered open dissent within his own party. Approval ratings are disappointing, and the midterm elections in November are fast approaching, threatening to turn him into a lame duck. Turning to foreign policy has often served US presidents as a way to escape troubles at home.

Greenland

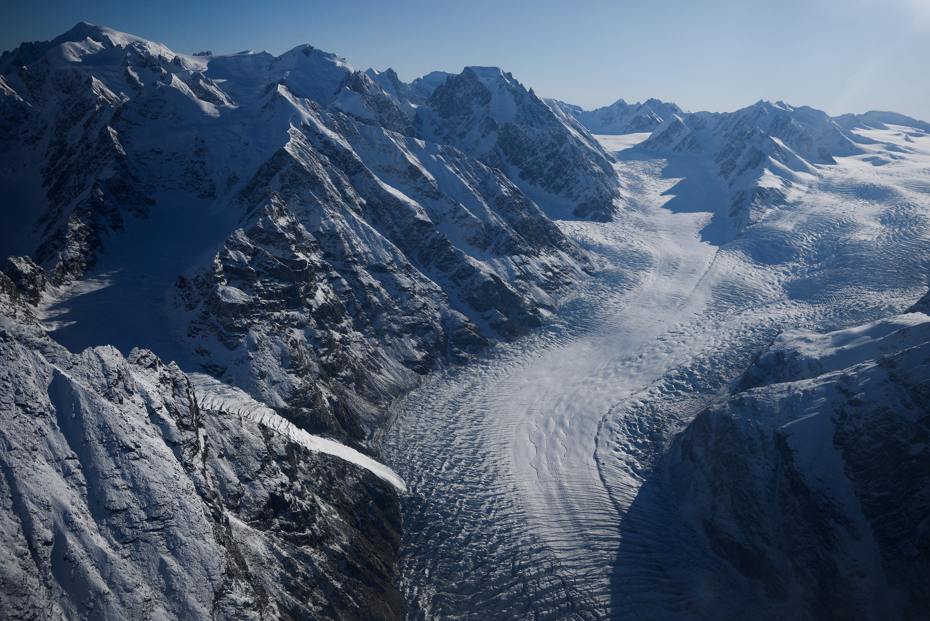

Despite its ironic name, Greenland is the world's largest island, spanning more than 2 million square kilometers, over 80 percent of which is covered in ice. Located in the North Atlantic between Europe and North America, it serves as a gateway to the Arctic. Yet only about 57,000 people live there. Greenland has been under Danish sovereignty since 1721 but enjoys broad autonomy with its own parliament, while Copenhagen retains control over foreign policy, defense and monetary policy. Relations between Denmark and the island's population have long been complex.

Why does Greenland matter? Beneath its ice, an estimated 25 of the 34 minerals classified as rare and critical are believed to be present. These raw materials are essential for electric vehicles, high-tech industries and defense systems. There is also speculation about potential oil and gas reserves. Today, most of these minerals are produced in China, giving Beijing control over global supply chains, something Washington is eager to change.

Resources are not the only draw. Global warming is melting glaciers and opening new shipping routes that could significantly shorten maritime trade between Europe and East Asia. Above all, there is security. Russia and China are increasing their presence in the Arctic, while the US has only three bases in the region and two icebreakers, though Trump has said he plans to expand the fleet. Greenland itself hosts a US early-warning system for intercontinental ballistic missiles, the result of a security agreement between Denmark and Greenland that regulates the American military presence on the island.

Talk in Washington about the need for control over Greenland, where the US already operates military bases, did not begin this week but very early in Trump's term. However, following the operation in Venezuela, renewed rhetoric about the island set off alarm bells in Copenhagen. Katie Miller, a former Trump adviser and the wife of Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, posted a map of Greenland in US flag colors on X with a single word: "Soon."

Her husband was asked on CNN whether the US ruled out using military force to take control of the island. He refused to commit. "No one will fight the US militarily over the future of Greenland," he said, even questioning Denmark's sovereignty: "What is the basis of Denmark's territorial claim? What gives it the right to hold Greenland as a colony?"

Pressure in Denmark has soared. Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen responded sharply in an interview with TV2: "The American president should be taken seriously when he says he wants Greenland. But if the US attacks a NATO country, everything stops, including NATO itself and the security built since World War II." Greenland's Prime Minister, Nielsen, addressed Trump directly: "Enough. Stop fantasizing about annexation."

Europe has rallied behind Denmark. Leaders of seven countries, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, the UK and Denmark, issued a joint statement declaring: "Greenland belongs to its people. Only Denmark and Greenland will decide matters concerning them."

Are we heading toward the unthinkable scenario of a military clash between the US and a NATO member on European Union soil? As much as anything can be ruled out in these "interesting" times, Washington has other avenues to pursue its goal. As an autonomous territory, Greenland could seek independence from Denmark through a referendum, an option it has so far not exercised despite political support among local parties for moving toward independence "someday."

In April, the New York Times reported that the White House had drawn up a persuasion plan aimed at Greenland's residents, including social media campaigns and economic incentives. Among them was an annual grant of $10,000 for every resident to replace Danish subsidies. "We support your right to determine your future," Trump told Greenlanders in a speech to Congress. "And if you choose, we welcome you into the US. We'll keep you safe. We'll make you rich."

In August, Danish broadcaster DR revealed that US citizens had carried out "covert influence operations" on the island to recruit support for secession from Denmark. An enraged Copenhagen summoned the senior US diplomat for a dressing-down.

Colombia

Colombia is another country that has is now on radar, perhaps an even more natural target than Venezuela for a president who has vowed to deal with countries that "poison" the American middle class by producing and trafficking drugs. Colombia is responsible for most of the world's cocaine production. Adding fuel to the fire is the intense personal animosity between Trump and Colombia's left-wing president, Gustavo Petro.

The two have exchanged a barrage of barbs over the past year, culminating in Petro's call for US soldiers to disobey Trump's orders during a visit to New York. Washington responded by revoking his visa.

This week, aboard Air Force One, Trump did not hold back. "Colombia is very sick, run by a sick person who loves producing cocaine… and he won't be doing it much longer," he said. Asked about a military operation in Colombia, Trump replied: "Sounds good to me." Petro reacted furiously, declaring that despite having sworn never to "take up arms again," he would do so "for the homeland if necessary."

Despite the heated rhetoric, the two countries continue to cooperate in the fight against drugs. Elections are scheduled in Colombia in May, and Trump is hoping they will produce a president more amenable than Petro, the leftist standard-bearer on the continent. That political calendar could delay any decision on military action.

Mexico

While Trump said this week that the cartels "run" Mexico and that "something will have to be done," relations between the two neighbors are fundamentally different from those between the US and Venezuela or Colombia. President Claudia Sheinbaum is walking a fine line. On one hand, she sharply condemned the operation in Venezuela. "We categorically reject intervention in the internal affairs of other countries. The history of Latin America is clear: intervention has never brought democracy," she said. On the other hand, she has tightened security cooperation with Washington, extradited senior cartel figures to the US and launched a military operation against the Sinaloa cartel.

Still, the legal groundwork for US action in Mexico has been laid. Trump has designated the cartels as terrorist organizations, and the fentanyl crisis, the deadly synthetic drug Trump has called a "weapon of mass destruction" flowing north and killing tens of thousands of Americans each year, provides what he presents as public justification. Over the past year, reports have repeatedly surfaced about operational preparations for such an intervention.

Cuba

Cuba, the Caribbean island nation that since 1960 has symbolized communist defiance in the face of "American imperialism," may be the most vulnerable on the list. It was heavily dependent on Venezuela and, like it, is treated as a pariah by the West. The operation in Venezuela has already exacted a heavy price from Havana. Thirty-two Cubans were killed in the raid, all members of armed forces and intelligence agencies providing security for Maduro. The Cuban government declared days of national mourning.

Beyond the casualties, the real blow is economic. Cuba relied for years on cheap Venezuelan oil. Now, with the US controlling Venezuela, the tap could be shut off. "Cuba is going to fall," Trump predicted to reporters. "It only survived because of Venezuela. Now they won't have that money." Senator Lindsey Graham, standing beside him, added that the days of the "communist dictatorship" were numbered.

The fall of Cuba, beyond the symbolism of the disappearance of a regime that is a living fossil of the Cold War, may be especially close to the heart of the man who appears to wield the greatest influence over the president: Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the son of Cuban refugees. Rubio, widely seen as the biggest winner of the Venezuela operation, said at the post-operation press conference: "If I were living in Havana and part of the government, I'd be a little worried."