On March 24, 2025, the prestigious magazine The Atlantic exposed one of the biggest scandals in American national security history, a field not unfamiliar with scandal. Jeffrey Goldberg, the magazine's editor-in-chief, published how Mike Waltz, President Donald Trump's National Security Advisor, mistakenly added him to a Signal group called "Houthi PC small group" – a group that included 18 senior administration officials.

Goldberg watched in real time as senior administration officials received briefings on a military strike against the Houthis in Yemen, including targets, weaponry, timing, and sequence of operations. None of them knew that a senior journalist was in the group. This was the Trump administration's second term's first "wing stroke." Waltz paid the price and was moved to the position of UN Ambassador.

The person who reaped the benefits of the embarrassing situation and was appointed to the position of National Security Advisor in Waltz's place was Marco Rubio, who simultaneously served as Secretary of State. In doing so, he became the first person after the mythological Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to hold both positions simultaneously. Rubio's senior status with Trump is particularly surprising if you go back about a decade to the two men's contest in the Republican Party primaries and to the confrontations between them that sometimes deteriorated into ugly mudslinging.

Despite Rubio's upgrade after "Signal-gate," many saw this as another instance of Trump's contempt for Washington's bureaucracy. This was not without foundation. At that time, aggressive budget cuts were making names in the federal administration, and important diplomatic matters were divided between the president's personal envoys – chief among them his close friend United States Special Envoy to the Middle East Steve Witkoff – and it appeared Trump sought to keep official advisors' feet out and cut the path in the regular work processes of executing his policy.

Just over three weeks ago, on January 3, Delta Force fighters burst from the darkness into the hiding place of Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores. At the end of this operation, the two landed on US soil and were transferred to a secure prison in Brooklyn. At a press conference, Trump declared that the US would "manage" Venezuela. In a post a few days later, he responded to someone who called Rubio "the de facto president of Venezuela" and wrote, "Sounds good."

Everything from above

This was indeed Rubio's greatest victory, not only within the current administration but in general. Rubio (54, married and father of four) was born in Miami to parents who emigrated from Cuba shortly before it fell to communism in the 1950s. His father worked as a bartender, his mother as a housekeeper, and the "American Dream" was for him a biography, not a slogan. In the family living room, politics was not an abstract concept but a living memory – stories of lost freedom and a regime that turned millions into refugees. This was his first political education.

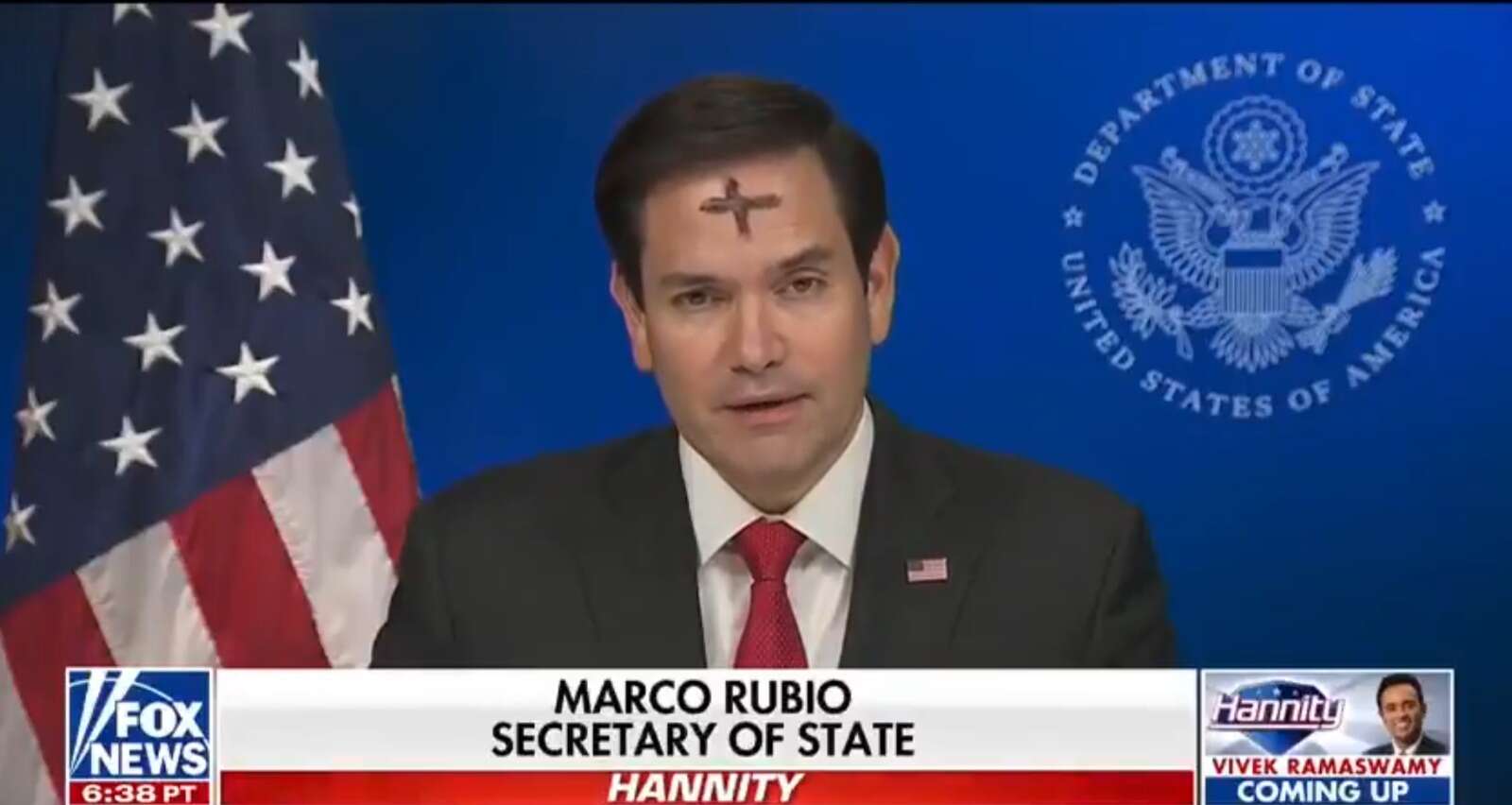

His Christian faith is one of the defining factors of his character and his politics. "His faith, his Catholicism has really defined his political life," a senior State Department official who has worked alongside Rubio for more than two decades told Israel Hayom. "It is the base, the foundation of who he is." Last March, Rubio appeared in a Fox interview with a cross mark in ash on his forehead, as is Catholic custom on Ash Wednesday, the day that opens the fast days before Easter.

But here too, there is complexity. Rubio underwent a stormy spiritual journey – born Catholic, baptized as a Mormon as a child, returned to Catholicism, and in the 2000s was drawn to a Baptist megachurch in Miami. To many, his speech style recalls the sermons of an evangelical preacher, and he himself is staunchly opposed to abortion. In a way, he represents a union of the central religious conceptions in American public life.

In his farewell speech from the Florida House of Representatives in May 2008, Rubio addressed his faith. "God is real," he declared fervently. "I don't care what courts across the country say. I don't care what laws we pass. God is real. You can't pass a ruling that will distance God from this building. He doesn't care about the Florida Supreme Court. He doesn't care about the US Supreme Court."

He continued, "God loves every person on the face of the earth, whether you're passing through and whether you're behind bars. He doesn't care if you have a visa to be here legally. He loves you. He doesn't care if you committed the most abhorrent act that violated human laws. He loves you."

"Small hands"

Rubio's political ascent was rapid. In his 20s and 30s, he advanced in Florida politics – city council member, state House member, and at age 35 was already House Speaker, the youngest and first Hispanic in the position. Jeb Bush, former Florida Governor and son of the 41st president, was his mentor and saw him as the party's future.

In 2010, he was elected to the Senate on the wave of the "Tea Party" – a conservative populist movement, a harbinger of the MAGA movement – that opposed the expansion of the federal government after the 2008 economic crisis. In Washington, he built a profile as a serious legislator on foreign and security issues, was considered a brilliant speaker, and was perceived as a natural candidate for Republican Party leadership.

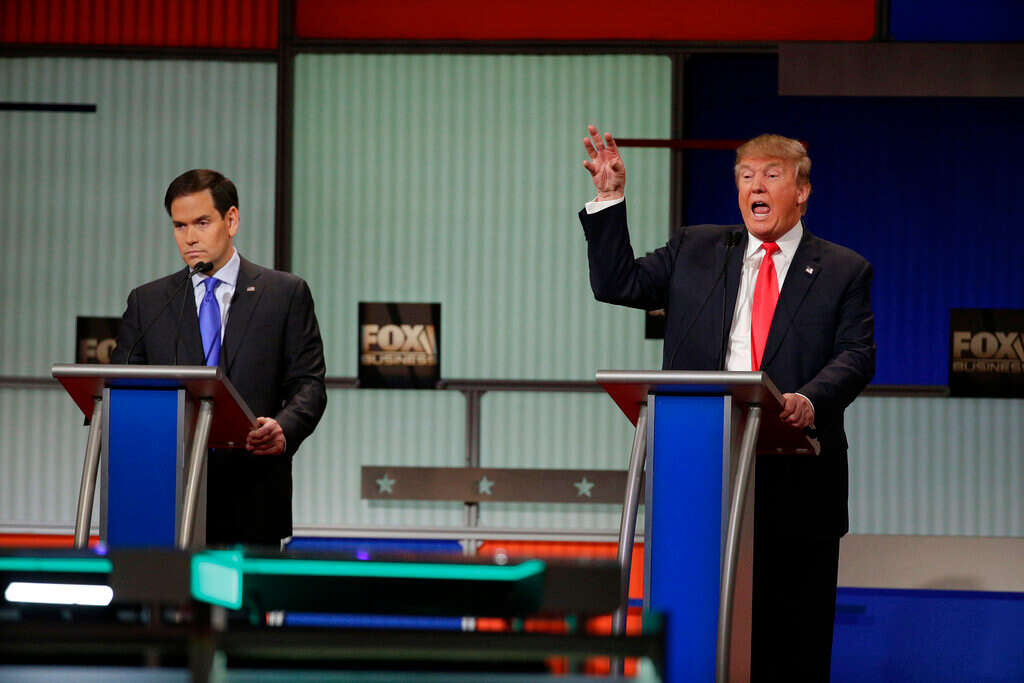

In 2016, Rubio ran in the Republican presidential primaries. His polished image, political professionalism, and conservative ideas clashed head-on with Donald Trump, the populist comet that blazed through American political skies. Rubio called him a "con man," warned he was "unfit to be president," and described him as a "danger to the conservative movement." Trump didn't remain indebted. He gave Rubio the nickname "Little Marco" and described him as a "lightweight" and an "establishment puppet."

The exchange of blows between Trump and Rubio was violent, even by Trump's standards and even by the ugly primaries of 2016. Rubio took upon himself the war against the populist candidate that the Republican establishment didn't know how to deal with. In a February debate, he hurled at Trump, "If you hadn't inherited $200 million, you'd be selling watches."

At a campaign rally, he went below the belt, mocking his allegedly small hands. "He's taller than me, so I don't understand why his hands are the size of someone 1.57 meters (5 feet 2 inches) tall. And you know what they say about men with small hands – you can't trust them." Trump, unaccustomed to defending himself, was forced to respond at a Detroit debate. "Look at these hands, are they small? If they're small, something else is probably small. I guarantee you there's no problem."

In another part of a debate, the two clashed over foreign policy. When Trump boasted he could negotiate with the Palestinians, Rubio interrupted him, "The Palestinians are not a real estate deal, Donald." Trump replied, "You can't negotiate. With your thinking, you'll never bring peace."

It didn't work. On March 15, Rubio lost his home state of Florida and announced his withdrawal from the race. "I'm not going to be anyone's vice president," he told reporters with visible disappointment. "I will finish my term in the Senate and in January I will be a private citizen."

That painful moment passed, and the political bug wouldn't let Rubio retire. "He put his head down, he did the hard work as a senator, and he learned to adapt and be patient and, you know, support the party and figure out how his, you know, foreign policy beliefs fit into a new era of the Republican Party under Trump," the senior official told Israel Hayom. "He could have walked away from, from public life, like a lot of people did that were beaten by Trump."

Instead of disappearing from political life like many Trump trampled on his way, Rubio joined the winners, in his own way. The neoconservative conceptions he championed – American dominance, war against hostile regimes, free market, projection of force – became a dirty word in the new Republicanism that advocated isolationism and ending the "endless wars." Rubio became a "translator" of the old party to the new world. Instead of "spreading democracy," he spoke of "protecting national security;" instead of ideological intervention, war against "drug cartels poisoning the American people and the middle class." The goals remained similar – toppling a communist and hostile regime in America's backyard – the language changed.

The same senior official adds, "I see the happy warrior that I met, you know, in his 20s, it's still the happy warrior in his 50s that he is today. In his nature, he is hopeful, he's optimistic, he's funny."

The confrontation with Witkoff

The beginning of his path in the administration was, as mentioned, difficult, and more precisely, boring. Steve Witkoff, the real estate billionaire and friend from Manhattan, expanded from his small office at the State Department his areas of occupation from Gaza and Iran to the war in Ukraine. It appeared this man, who never dealt with diplomacy, was the de facto Secretary of State. Witkoff flew on his private plane to meetings with Putin and senior Arabs and scheduled meetings with leaders without updating Rubio.

In late November and early December, Witkoff hoped to restart talks to end the war in Ukraine after the success in Gaza. Already then, his pro-Russian tendency was a topic of conversation, and eyebrows were raised when he arrived at a Kremlin meeting without his own interpreter and relied on translation services the Russians were happy to provide. The plan was leaked to the media, and its tilt toward Putin sparked a global storm. Bloomberg obtained a conversation in which Witkoff offered his Russian counterparts the chance to coordinate a phone call between Trump and Putin just before Ukrainian President Zelenskyy's planned visit to the White House – a move the Russians hoped would strengthen their bargaining position.

In a panicked manner, it was decided to hold talks with Ukrainian representatives in Geneva. According to NBC, at that time, Rubio was preparing for the wedding of acquaintances in North Carolina, where his two daughters served as bridesmaids, when he learned that Witkoff was already on his way to Geneva. Without him. This wasn't the first time. In April, before talks in Paris, Witkoff scheduled a meeting with President Emmanuel Macron without informing him. The French Foreign Ministry informed his people they needed Witkoff's approval for Rubio to join – a humiliating moment for the Secretary of State.

Rubio left quickly and managed to arrive on time. In Geneva, he succeeded in changing many of the harshest demands on Kyiv that Witkoff had included in the proposal. That diplomatic effort to bring an end to the war in a way that would put Ukraine at a disadvantage was thwarted. This was a live demonstration of the difference between "Trumpist" diplomacy – businesslike, direct, impatient with protocols, often hostile to allies – and that of Rubio.

"Rubio harnessed the experience he accumulated in the Senate Foreign Relations and Intelligence Committees to translate Trump's instincts into foreign policy. He became a factor that balances between the isolationists in the party and the need to project force," explains Prof. Udi Zomer, head of the Barak Center for Leadership at Tel Aviv University.

Rubio's rising power did not escape the eyes of the tweeters. One meme became particularly popular. In February, during the stormy confrontation between Trump and Zelenskyy at the White House, Rubio was photographed sinking into the couch in the Oval Office, his hands folded and his face frozen, as if asking to be swallowed so as not to witness American diplomacy shatter into pieces. The cameras were riveted to the impolite collision between the world's most powerful man – and his deputy Vance – and the Ukrainian president, who was accused of "ingratitude" and expelled from the White House.

Over time, this photo actually became a joke about his rising power. Internet meme creators dressed him in the clothing of Venezuela's president, an Iranian ayatollah, an Eskimo in Greenland, and Fidel Castro's uniform, Cuba's mythological and late ruler. All these symbolized, as it were, the series of positions he would hold when the US would supposedly take control of these countries. Another satire site joked that "the White House announces that a million new jobs were added in December – all filled by Marco Rubio."

Regarding Cuba, Rubio is not in a joking mood. "

There's no way that Marco Rubio leaves being Secretary of State with the regime in Cuba intact. My eyes would be on Cuba next. It's personal for him," the State Department senior official told Israel Hayom. At the press conference after Maduro's capture, Rubio said, "If I lived in Havana and was in the government, I'd be worried."

However, meanwhile, and even more so this week, it appears American diplomacy has sailed again far from Rubio's warm breeze to Greenland's frost, as it is led by the president's old-new desire to take control of the Arctic island, and as is known, the president even refuses to rule out military action to achieve it.

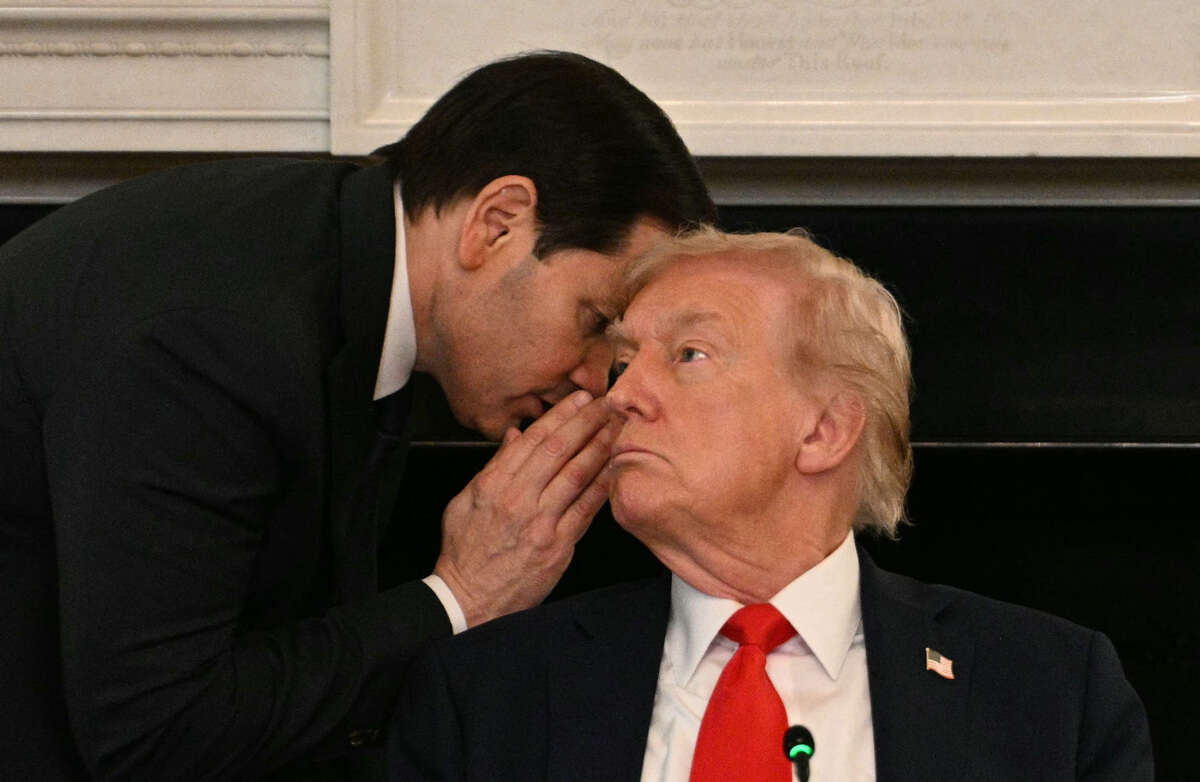

Rubio has already tried to calm the situation. In a conversation with French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot, he ruled out the possibility that "what happened in Venezuela will happen in Greenland," according to the latter's statement to local radio. But how much will Rubio succeed in deterring the president from pursuing the goal, whose achievement seems to endanger NATO's existence? "He's doing his best to rein in Trump's worst impulses," a European foreign minister told The New Yorker. "He understands what's at stake. He whispers in Trump's ear, but there's also a limit to his influence."

The inheritance battle

Three years before the end of the last term – another framework that has been undermined in the past year as Trump refused to rule out a third term – the president has already marked his two heirs, and not just once. In May, he mentioned Rubio before Vance when asked who would continue the MAGA movement. In August, he said Vance is "likely" the heir but added that Rubio "might connect with J.D. in some way."

J.D. Vance, unlike Rubio, is the natural and undisputed heir to the movement's leadership. The 41-year-old Vice President was born into poverty in a crumbling town in Ohio's Rust Belt to a mother addicted to drugs and a father who disappeared from his life. He described his childhood in a memoir that became a Netflix film ("Hillbilly Elegy") and a key to understanding Trump's voter base. While Rubio is a graduate of the old Republican Party who learned to speak in MAGA language, Vance is, as it were, the embodiment of the movement itself. He is the people for whom globalization, grand dreams of free markets, and the end of history didn't work.

For his part, Rubio is doing everything he can to shake off the expectation that he will compete head-to-head against Vance for the position and for the soul of the Republican Party. In an interview with Lara Trump, the president's daughter-in-law, he said Vance "would be a great candidate if he decides he wants to do it… He's a close friend, and I hope he intends to do it." Rubio added he would be satisfied with the Secretary of State position as "the peak of my career," but added that "you can't know what the future holds, you never rule things out… Things change very quickly."

For Israel, the possible battle between them could be fateful as ever, especially in light of the almost complete loss of Democratic support. "They represent two opposing approaches," says Prof. Zomer. "Rubio embodies the current that sees Israel as a vital strategic asset and a critical component in containing Iran and China – a Nixonian approach advocating active American involvement and broad military and diplomatic support as part of global hegemony. In contrast, Vice President Vance leads the America First line, which seeks to reduce American involvement in the world." He adds that "Vance may lead to an era of support from afar. As he expressed before the 2024 elections, if Israel wants to fight Iran, it can do so, but it's their decision and they'll have to bear the consequences."

An ominous sign was given by Vance in his recent appearance at a conservative conference in December, which took place while within the American right, a "civil war" was being waged between conservatives – represented by Ben Shapiro – and influencers like Tucker Carlson and Nick Fuentes, whose statements range from open antisemitism to burning anti-Israelism. "I didn't bring with me a list of conservatives to condemn or boycott," he said, in words that actually teach more than anything about which side he chose.

Finally, it appears everything depends on Trump himself. When the source who spoke with Israel Hayom was asked to assess who would win in a political battle between the two, he said, "Who knows? You know, six months is a lifetime in politics. A lot of it depends on the economy. And of course, it's up to Trump. You know, if he wants to endorse anybody, then it's game over. If he decides to stay out and let people, you know, do the 'Hunger Games' in the primary and watch it play out."