Hezbollah is no longer a single-patron proxy. Still aligned with Tehran but no longer dependent on it, the organization is adapting under pressure: battlefield attrition, leadership losses, financial strain, and a rare domestic challenge to its armed autonomy after Lebanon's new leadership ordered all weapons placed under state control - a demand Hezbollah rejected.

This shift was accelerated by a structural rupture. The collapse of the Assad regime in late 2024 disrupted Iran's primary land corridor to Lebanon, forcing adjustment. Iran moved to rebuild supply routes through Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean, elevating Turkey from marginal transit space to a critical node. Ankara simultaneously consolidated its role in post-Assad Syria through sustained military presence, advisory influence and expanding institutional and financial engagement, emerging as a secondary enabling channel for Hezbollah through converging operational interests.

The first observable indicator appeared in financial channels. On February 28, 2025, Lebanese authorities seized 2.5 million dollars from an individual arriving from Turkey, with sources confirming the funds were destined for Hezbollah. Israel later reported to the UN Security Council on additional cash flights along the same route in February 2025, indicating the seizure was part of a developing pipeline. In parallel, U.S. Treasury officials publicly identified Turkey as a transit point for funds moving from Iran to Lebanon. The route was treated as an active financial corridor.

In parallel, a sustained pattern was documented and verified. Senior Hezbollah operatives transited through Ankara and Istanbul under civilian cover, while Turkish intelligence personnel entered Beirut discreetly and proceeded directly to the Dahieh district. By late 2025, this movement had matured from quiet transit to overt interface, with Hezbollah-linked delegations visiting Turkey under political or quasi-diplomatic cover as Ankara increasingly framed itself as a mediator between Hezbollah, Syria and Iran. The sequence is consistent - meetings in Turkey, operational follow-up in Beirut, and direct access to Hezbollah's core command environment. This is not episodic contact. It establishes Turkey not as a formal sponsor, but as a permissive environment enabling Hezbollah's continued functionality under pressure.

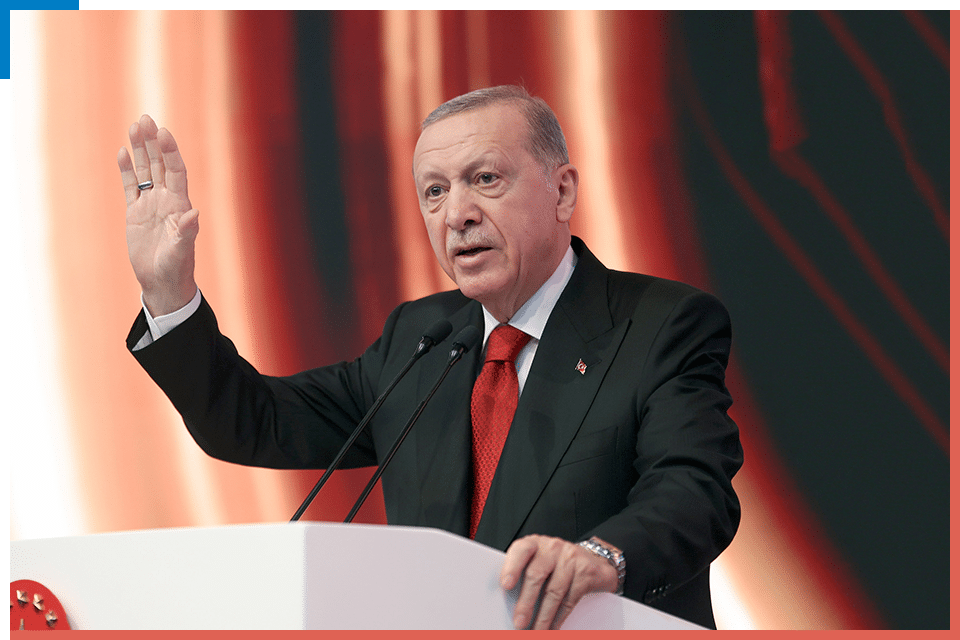

Ankara's messaging toward Beirut shifted accordingly. In a December 2025 call with President Joseph Aoun, President Erdogan tied Turkey's expectations of Lebanon directly to the protection of what Ankara defines as Turkish Cypriot interests. With that move, the Cyprus file was inserted into Lebanon's internal decision-making at the very moment Beirut was seeking to curb non-state veto power.

On November 26, 2025, Cyprus and Lebanon signed a long-delayed maritime demarcation agreement. For Cyprus, it provides legal certainty essential for offshore energy development and investor confidence. For Lebanon, it creates a lawful framework for exploration, risk reduction and regional energy cooperation after years of economic collapse. It is not a guarantee of resources, but a prerequisite for sovereignty expressed through law.

From Ankara's perspective, the agreement represents a strategic challenge. Turkey's policy seeks to prevent the Republic of Cyprus from converting international legality into regional leverage. The alternative has been pressure on partnerships, investor confidence and expanded military capabilities in the Turkish-occupied north of the island.

This expansion is concrete. Control of the Geçitkale air base has been transferred to the Turkish military. The site has hosted unmanned systems since 2019 and is being converted into a permanent drone hub. Turkish Bayraktar TB2 systems now operate routinely in Cypriot airspace, placing persistent ISR and strike-capable platforms over the same energy corridors anchored by the Lebanon-Cyprus agreement.

The threat to Cyprus is not theoretical. In June 2024, Hassan Nasrallah warned that Cyprus could be targeted if it facilitated Israeli military activity, stating it would be treated as part of the war. Cyprus rejected the premise, while the European Union affirmed that any threat to Cyprus constitutes a threat to the Union. The warning aligned with precedent: Hezbollah has previously used Cyprus as a logistics environment, including stockpiling more than eight tons of ammonium nitrate linked to the organization.

When Hezbollah's willingness to threaten Cyprus intersects with Turkey's military consolidation in the north of the island, a converging pressure axis emerges. From southern Lebanon to northern Cyprus, the same assets are exposed: energy infrastructure, maritime routes, investor confidence and Israel's extended security environment. Drones, sabotage and coercive signaling are sufficient when access exists and when at least one NATO member is willing to tolerate, and in some cases enable, the presence of actors that threaten EU territory.

Turkey's broader regional behavior completes the pattern. Ankara has shown how alignment with armed Islamist actors is translated into infrastructure: Hamas leadership operates openly from Turkey with diplomatic cover, while Ankara positions itself as mediator and stakeholder. In the Red Sea theater, a similar logic applied to the Houthis, where Turkish territory and companies facilitated financing and the transfer of dual-use components later incorporated into missiles launched toward Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Israel, even as Ankara publicly condemned Western strikes.

Syria served as the testing ground for this model, combining military presence, advisory roles and financial embedding to convert proximity into influence. Lebanon is now the most exposed arena: sovereignty is contested, Hezbollah resists disarmament, and Turkey's expanding footprint further narrows the state's ability to reclaim exclusive control over force.

Lebanon has encountered this dynamic before. The 1983 Israel-Lebanon peace agreement failed not because peace was unattainable, but because militias backed by external patrons retained veto power over the state. Hezbollah's current transition adds a new layer of risk. An organization under pressure does not moderate; it diversifies. Financial flows through Turkey, rebuilt maritime and air corridors, diplomatic pressure tying Lebanon to Ankara's Cyprus agenda, military consolidation in the Turkish-occupied north of Cyprus, and direct threats against Cyprus together form a single trajectory.

The precedent is set. In September 2024, Israel eliminated Hassan Nasrallah, establishing that when threat chains converge, leadership and enabling systems are treated as one.

That standard has already been applied beyond Hezbollah itself. Senior Iranian operatives tied to Hezbollah and the Quds Force have been eliminated in Lebanon and Syria, making clear that exposure is defined by responsibility, not nationality or geography.

When activity is sustained through foreign cover or transit, assumptions of immunity collapse. Jerusalem's conduct - not declarations - draws the line.

Shay Gal is a strategic analyst in international politics, crisis management and strategic communications, working globally with a focus on geopolitics, power projection and public diplomacy, and their impact on state decision-making and strategic behavior.