A fundamental disconnect exists between genocide allegations against Israel and the actual casualty figures in Gaza, exposing critical flaws in accusations of systematic extermination, according to an op-ed published The New York Times conservative columnist Bret Stephens. In his piece in the paper, he challenges critics to reconcile Israel's overwhelming military capabilities with relatively restrained casualty numbers if genocide is truly the objective.

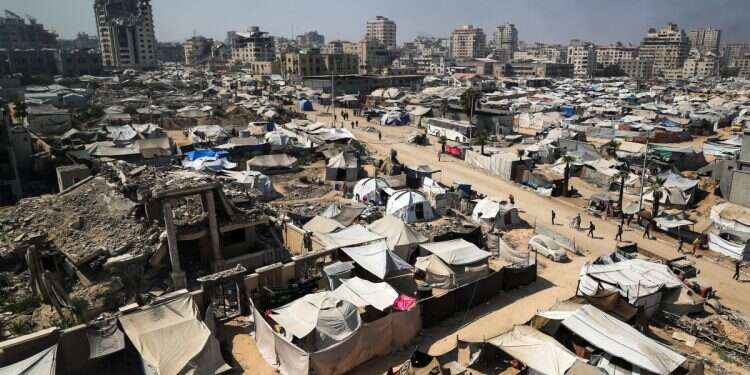

The examination reveals that approximately 60,000 deaths reported by Gaza's Hamas-controlled Health Ministry over nearly two years represents a fraction of what genuine genocidal intent would produce. "If the Israeli government's intentions and actions are truly genocidal – if it is so malevolent that it is committed to the annihilation of Gazans – why hasn't it been more methodical and vastly more deadly?" Stephens writes. "Why not, say, hundreds of thousands of deaths, as opposed to the nearly 60,000 that Gaza's Hamas-run Health Ministry, which does not distinguish between combatant and civilian deaths, has cited so far in nearly two years of war?"

The analysis demonstrates Israel's capacity for exponentially greater destruction than what has occurred, noting the country's position as the region's dominant military power following successful operations against Hezbollah and Iran. The New York Times piece emphasizes that Israeli forces routinely warned civilians before strikes rather than bombing without notice, and chose ground operations that exposed hundreds of Israeli soldiers to fatal risks instead of relying solely on airpower.

External constraints haven't limited Israeli military options significantly, according to the columnist's assessment. President Donald Trump has publicly endorsed relocating Gaza's entire population and threatened severe consequences if Hamas fails to return hostages. Economic pressure through boycotts has proven ineffective, with Tel Aviv's stock exchange performing as the world's best major index since October 7, 2023.

Legal definitions of genocide require demonstrable intent to destroy specific groups "as such," based on ethnic, racial, religious or national identity, according to UN conventions cited in the analysis. "Genocide does not mean simply 'too many civilian deaths' – a heartbreaking fact of nearly every war, including the one in Gaza," Stephens explains in The New York Times. "It means seeking to exterminate a category of people for no other reason than that they belong to that category: the Nazis and their partners killing Jews in the Holocaust because they were Jews or the Hutus slaughtering the Tutsis in the Rwandan genocide because they were Tutsi."

The piece contrasts Hamas' October 7 massacre with Israeli military objectives, arguing that terrorists deliberately murdered Israeli civilians based purely on their identity while Israeli operations target Hamas infrastructure and seek hostage recovery. Historical precedent supports this distinction, with massive Allied bombing campaigns killing over one million German civilians during World War II without constituting genocide because the intent focused on defeating Nazi forces rather than exterminating Germans for their ethnicity, Stephens argues.

Gaza's destruction levels and inflammatory statements by some Israeli politicians fail to establish genocidal intent, the columnist argues. "Furious comments in the wake of Hamas's Oct. 7 atrocities hardly amount to a Wannsee conference, and I am aware of no evidence of an Israeli plan to deliberately target and kill Gazan civilians," Stephens writes in The New York Times.

The analysis acknowledges significant destruction while recognizing that bungled humanitarian operations, undisciplined soldiers, misdirected strikes and vengeful political rhetoric represent typical warfare realities rather than systematic extermination campaigns. Military forces throughout history have committed individual war crimes without their conflicts constituting genocide, according to Stephens.

Hamas' tactical approach creates unprecedented combat challenges by inverting established civilian protection protocols, the piece explains. Ukrainian civilians shelter underground while military forces operate above ground during Russian attacks, but Hamas fighters hide in tunnel networks while keeping civilians exposed on the surface. "In Ukraine, when Russia attacks with missiles, drones or artillery, civilians go underground while the Ukrainian military stays aboveground to fight. In Gaza, it's the reverse: Hamas hides and feeds and preserves itself in its vast warren of tunnels rather than open them to civilians for protection. These tactics, which are war crimes in themselves, make it difficult for Israel to achieve its war aims: the return of its hostages and the elimination of Hamas as a military and political force so that Israel may never again be threatened with another Oct. 7," Stephens argues in The New York Times.

The columnist draws direct parallels between Gaza operations and US-supported Iraqi campaigns against ISIS in Mosul during 2016-2017 under Barack Obama and Trump administrations. American airstrikes leveled entire city blocks during the nine-month operation, with one March incident reportedly killing 200 civilians in a single strike. "This fight, carried out over nine months, had broad bipartisan and international support. By some estimates, it left as many as 11,000 civilians dead. I don't recall any campus protests," Stephens observes.

The genocide allegation serves dual political purposes beyond legitimate legal concerns, according to the analysis published in The New York Times. Anti-Zionist activists exploit the charge to equate modern Israel with Nazi Germany, legitimizing renewed antisemitic attacks against Jewish supporters of Israel. Simultaneously, promiscuous application of genocide terminology threatens to dilute the term's significance for identifying actual systematic extermination campaigns.

"If genocide – a word that was coined only in the 1940s – is to retain its status as a uniquely horrific crime, then the term can't be promiscuously applied to any military situation we don't like," Stephens concludes in The New York Times. "Wars are awful enough. But the abuse of the term 'genocide' runs the risk of ultimately blinding us to real ones when they unfold."

The analysis suggests that while most Israelis support ending the Gaza conflict, misapplying genocide charges undermines rather than advances peaceful resolution. "The war in Gaza should be brought to an end in a way that ensures it is never repeated. To call it a genocide does nothing to advance that aim, except to dilute the meaning of a word we cannot afford to cheapen," the columnist writes.