The relationship between diaspora Jews and Israelis has always been two things: strong and complicated. Yet, as someone who grew up in the diaspora and moved to Israel over seven years ago, I see more than ever the growing misunderstanding and how out of touch both groups are between one another.

From the earliest days of Zionism, debates raged between those in the diaspora and those in Israel and Ben-Gurion himself often clashed with American Jewry, warning that life in the diaspora came with risks of detachment. These tensions are not new, but they have intensified in an age where social media gives every voice a megaphone, regardless of proximity to the struggle.

Israel is the homeland of the Jewish people, and October 7 demonstrated more than ever that what happens here affects Jews everywhere. This is part of the reason why certain token Jewish actors like Mandy Patinkin and Miriam Margolyes feel entitled to blame Israel or Netanyahu for the antisemitism Jews are facing worldwide (which is absurd, as it amounts to blaming Jews for antisemitism). It is also why many diaspora Jews feel deeply connected to what is happening in Israel, as though it affects their daily lives. The Jewish nation is small, and most diaspora Jews have some family or connection to Israel, where nearly half of the global Jewish population lives.

It was only after I moved to Israel, after I began to understand the nuances of Israeli society, learned Hebrew, followed local news closely, spoke directly with military and government officials, and as a journalist visited places like the West Bank and the Gaza border, that my understanding of Israel and the Middle East truly shifted. This was not a shift toward one political side but rather an upgrade, a deeper awareness of the region and the complexities Israelis face. Looking back at my views in the diaspora, I now see myself as a well-intentioned but naïve version of me, lacking the knowledge and context to comment meaningfully.

This is the message to so many who feel a "moral responsibility" to weigh in on the war between Israel and Hamas, even though they have never set foot in the region and could not point out Gaza on a map or explain which river and sea they are chanting about. And while most diaspora Jews who comment on Israeli affairs have likely visited, that does not give them the authority to dictate or misrepresent our internal struggles.

Israel has been enduring nearly two years of war. Before that, the judicial reform crisis nearly pushed us to civil war. Israelis have been grappling with weak and incompetent leadership, and now we stand at another crossroads: a potential hostage deal or a new Gaza maneuver.

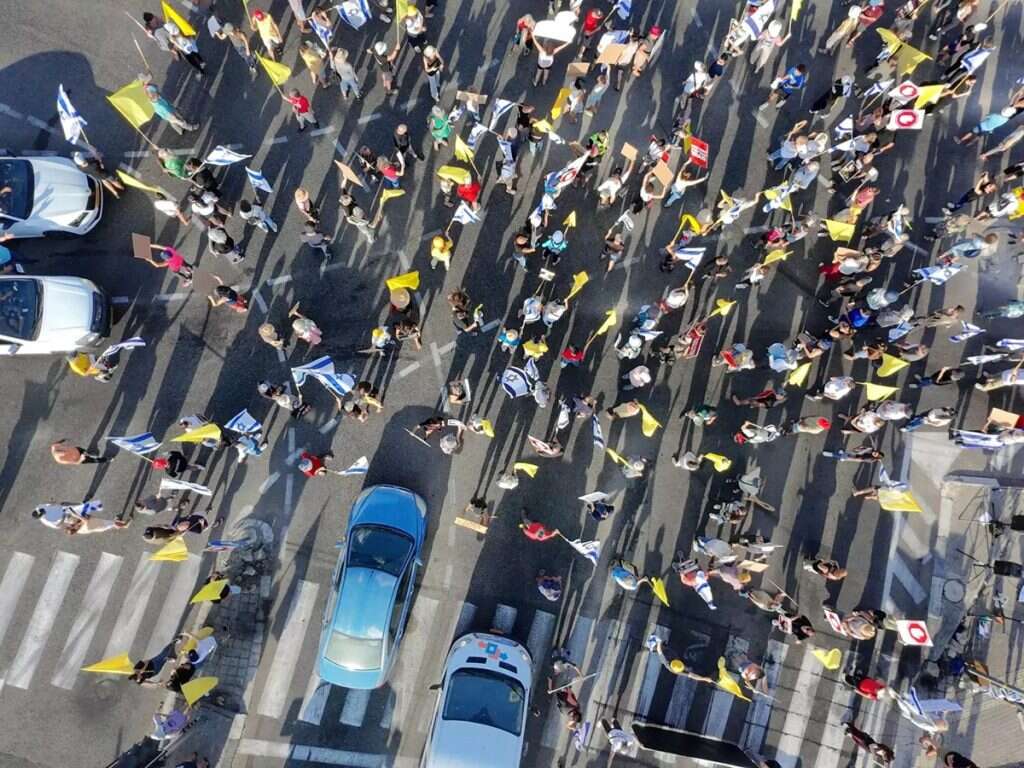

During the reform protests, I saw self-proclaimed "influencers" spreading falsehoods, portraying demonstrators as merely "angry leftists" instead of the diverse mosaic of Israelis fearful for their democracy. After six hostages were murdered by Hamas, Israelis filled the streets in outrage, many furious that government delays had prevented a deal that could have saved lives. Yet from abroad, some dismissed these demonstrations as misguided. When a previous hostage deal collapsed in March, activists outside Israel cheered the government's renewed fight against Hamas, even though polls showed most Israelis wanted the deal to continue. And now, as many fear that new operations in Gaza could endanger the remaining hostages, Israelis are again taking to the streets to make clear that the majority supports ending the war in order to bring the hostages home. Every poll since May 2024 shows this, along with a collapse of faith in the government's ability to deliver.

Agree or disagree with the Israeli public, it is unacceptable to misrepresent their actions or reduce them to "a bunch of angry leftists" or, conversely, dismiss those who oppose ending the war as "Kahanists" who want hostages dead. Such simplifications are dishonest and erase the complexity of a nation in pain.

Diaspora Jews absolutely have the right to care about what is happening in Israel. But they should not misrepresent events, nor claim to know what is best for Israelis better than the people who actually live here.

Moshe Emilio Lavi, whose cousin Omri Miran remains in Hamas captivity, put it best on X: "If you want to comment on our internal affairs, ethos, and social contract, then move to Israel, conscript to the IDF or national service, learn our modern language, culture, society, and ethos, and maybe live on the border with your life and your family's life on the line. Until then, your opinions on our domestic discourse are entirely misplaced."

The relationship between diaspora Jews and Israelis is complex, as is natural in a global family. And while Israelis can always improve in how we support our Jewish brothers and sisters abroad, one truth remains clear: those on the front lines must have the loudest voice in deciding their own future.