Israeli baseball chief Ari Varon believes children currently playing in Ra'anana will represent Israel at the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics, as he spearheads an ambitious transformation of the sport from its American immigrant roots into a distinctly Israeli athletic culture.

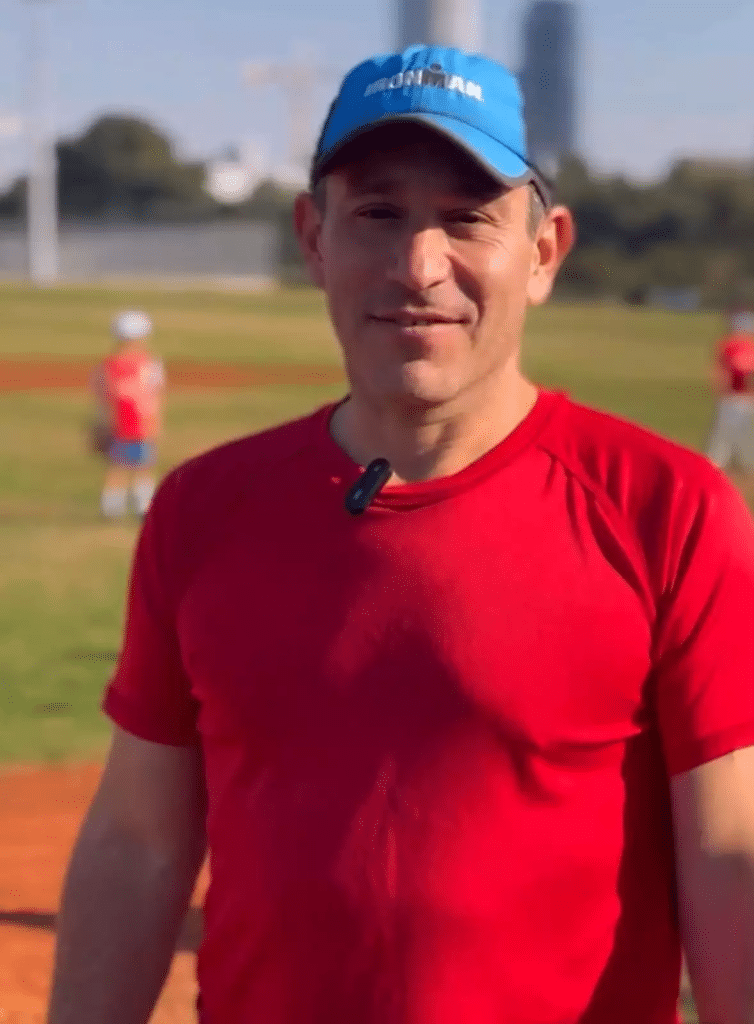

The head of the Israeli Baseball Association entered his role with passionate determination to expand the sport's reach beyond its traditional base among North American olim. Varon, a Tel Aviv resident married with three children, made aliyah from Oregon at age 13 and discovered baseball accidentally at a Ra'anana training session.

"For me, baseball is much more than a game," Varon said in an exclusive interview with Israel Hayom. "It's a place where I learned values, gained lifelong friends, and now I want to pass that on to the next generation in Israel."

The sport faces a critical juncture following its historic success at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics and its restoration to the Olympic program for Los Angeles 2028 after being absent from the Paris 2024 Games. Varon sees this as a dual opportunity to solidify Israel's national team internationally while demonstrating to Israeli children the potential heights they can reach.

Baseball provided Varon with essential integration tools as a teenage immigrant who barely spoke Hebrew. "I arrived in Israel as a teenager, hardly knowing a word of Hebrew," he explained. "Baseball was the place where I found a common language. It didn't matter if I didn't speak Hebrew - on the field, everything was clear: rules, team, responsibility. It gave me an incredible sense of belonging."

The association head emphasizes the character-building aspects of baseball for his own three children and the next generation. "I want them to have the opportunity to grow up with the values that baseball provides: discipline, cooperation, and also patience," Varon said. "It's not a game of immediate solutions, but of planning, strategic thinking, and proper utilization of opportunities."

Leagues, fields, and Olympic dreams

Varon assumed his position at a critical moment for Israeli baseball. While the sport gained international exposure through its historic Tokyo 2020 success, domestic conditions remain far from ideal. The number of fields is limited, youth leagues struggle for budgets, and schools barely recognize the sport.

"I want baseball to be accessible to every child in Israel who wants to try," he declared. "That means more fields, more coaches, and an organized program that connects the sport to the education system. It's impossible for this to remain an 'American niche' game – there's real potential here, and children who come fall in love with it very quickly."

His vision extends beyond Israel's borders. With baseball's return to the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics, Varon sees a double opportunity to continue establishing the national team globally while showing Israeli children where they can reach. "Anyone who saw the national team in Tokyo knows this isn't fantasy," Varon projects optimism. "Israel can compete with the greats for real. My goal is that we'll reach Los Angeles with a young and hungry squad, one that represents not only American immigrants but also the natives who learned the game here."

One of Varon's greatest challenges involves establishing a different sports culture in Israel than the one in which he grew up. In the United States, baseball is almost a religion with packed stadiums, millions of viewers, and an entire language of statistics and data. In Israel, it remains primarily known to North American olim who must still build its popularity.

"I understand why some people say baseball is too slow," he acknowledged with a smile, while believing the perception can change. "Those who understand the game discover a whole world. There's deep tactical thinking here, dramas that unfold in one small moment, and most importantly, it's a team game. You can't succeed in it alone."

According to Varon, Israeli culture can provide an interesting twist to the game. "There's energy here, creativity, healthy 'chutzpah'. That's what's needed to develop the Israeli style in baseball, one that doesn't try to copy the Americans but finds its own original path."

When asked what drives him to invest so much time and energy, Varon hardly hesitates. "I feel a mission," he said simply. "There were moments when I asked myself why I'm doing this, since it's not always simple. But then I see a ten-year-old child stepping onto the field for the first time, hitting the ball, and feeling that excitement, and it reminds me of myself at that age. If I succeed in giving another generation that experience, I've done my part."

The challenges are clearly numerous: raising budgets, convincing decision-makers to invest in fields, and expanding the fan base in a country where sports already compete for attention against countless other options. Nevertheless, Varon remains convinced the right approach is slow and steady, with organized long-term investment.

Varon concluded: "We're not looking for shortcuts. The goal is to build stable foundations, so that baseball remains here for decades more. My dream? To see a packed baseball stadium in Tel Aviv, with families coming to enjoy the game, and knowing that the children who played today on Ra'anana or Petach Tikva fields are those representing Israel on the Olympic stage in Los Angeles."