Even before they truly began, the nuclear talks appeared on the brink of collapse, with a moment in which it seemed the sides might not meet in Oman or anywhere else. The core of the crisis lies not only in gaps over substance, but in a deep and unbridgeable divide in how each side perceives the other.

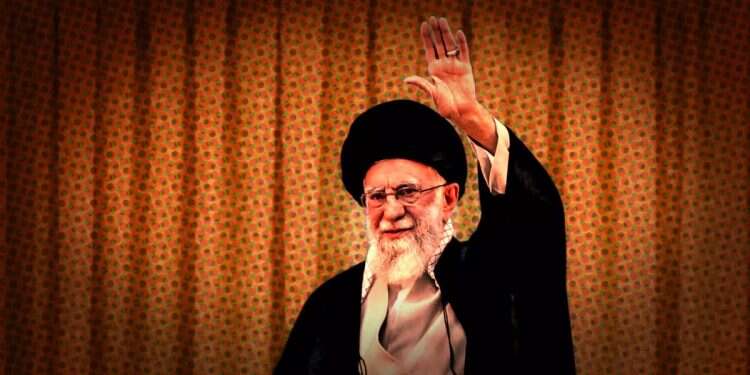

To understand the crisis, it is necessary to enter the mindset of Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is inherently suspicious of the US in general and of the American president in particular. From his perspective, he arrives at this moment after years of developments he interprets as part of a comprehensive conspiracy against the regime, most recently the 12-day war and the wave of protests across Iran. Seen through this lens, it is clear why he has no intention of compromising on the regime's core principles. In his view, it is entirely possible that the US has already decided to strike, or at the very least is acting together with its regional allies to deprive Iran of its ability to defend itself. Faced with this reality, he prefers to risk an attack rather than submit.

On the other side, the American administration operates under the assumption that Iran has been significantly weakened by the military confrontation and by internal unrest. In Washington's assessment, a combination of military pressure and a show of force will ultimately compel Tehran to accept US demands, not only on the nuclear issue, but also on its missile program and network of regional proxies.

This perceptual gap prevents the sides from even sitting down to talk, because at a fundamental level they have nothing to discuss. It is possible that neither side seeks escalation and that both would prefer negotiations that end in compromise, but their respective perceptions of each other, and of themselves, make such an outcome unattainable.

It is easy to dismiss the way Iran views itself, but anyone attempting to anticipate its next moves must understand that from the regime's perspective, its positions cannot be separated from the belief that it "stood firm" both in the military confrontation and in the face of protests, which it sees as part of a broad Western plot to overthrow it.

Accordingly, even if the talks do take place and survive the current crisis, there is a high likelihood they will run aground once one side attempts to bend the other to its will, a direct result of starting positions that almost guarantee failure. As long as Khamenei remains at Iran's helm, regardless of what the US does, it can be expected that he will not cross the line he has already defined as surrender.

Iran has no future in its current state, but for the supreme leader, loyalty to the revolution's ideology outweighs considerations of prosperity or stability. Abandoning these principles would, in his eyes, amount to abandoning the revolution itself.

The problem is that even the collapse of the regime does not necessarily promise a stable or democratic Iran, and may well produce the opposite outcome. Under present circumstances, an escalation appears inevitable, though not necessarily imminent. The US can still leverage its massive military presence in the Gulf to project power and pressure the regime, thereby giving mediators another opportunity. In practice, however, the diplomatic track currently appears devoid of real viability.